- Home

- Herbert Strang

Bright Ideas: A Record of Invention and Misinvention Page 5

Bright Ideas: A Record of Invention and Misinvention Read online

Page 5

*II*

Spring and summer had been very dry, and Farmer Trenchard's fields,lying on a rocky upland, gave promise of but an indifferent harvest.The growth was thin, the stalks were short and yellow, the husks lean.The farmer had almost given up hope of his cereals, and his root cropscould only be saved if the drought was soon broken.

On the morning following the affair of Nahum Noakes's bumps Mr.Trenchard was walking along the edge of one of his fields, lookingdisconsolately at the drooping upper-growth of the carrots. Eves andTempleton were hoeing some little distance away.

"Here's old Noakes," said Eves, suddenly. "Wonder if he's come to grouseabout yesterday?"

Mr. Noakes, dressed as usual in his rusty frock-coat, but wearing a newstraw slouch hat--his old one had not survived its bath of soot--wasshambling up the field to meet the farmer.

"Marnen, neighbour Trenchard," he said.

"Marnen, Mr. Noakes," returned the farmer, with the air of timidity thatmarked all his intercourse with his neighbour. The two men stoodtogether, Noakes smug and self-satisfied, Trenchard downcast and almosthumble.

"It do seem you'd be the better for a drop of rain," Noakes went on."The ground be dust dry. Them there carrots baint no good."

"True; I'm afeared 'twill be a bad year wi' me."

"Well, we're in the hands of Them above," said Noakes, smiling andrubbing his hands slowly together. "The old ancient men of Egypt hadtheir lean years and their years of plenty; we can't look for nodifferent in these here end o' the world times."

"Ah, Mr. Noakes, I don't gainsay 'ee, but 'tud hev made all thedifference to me, a good moist season. I be afeard I shall have to axe'ee----"

"Not a word, neighbour. Sufficient unto the day, you know. Not butwhat 'tis a misfortune to 'ee, but things may take a turn."

He thrust his hands into his pockets and stood for a few momentsscanning the fields; then after a word or two of a general nature movedaway, without having appeared to notice the two boys.

"Cut dead!" said Eves with a grin. "A good thing too; I loathe thefellow. Poor old Trenchard will be wretched all the rest of the day. Iwonder why he always looks so hang-dog when Noakes is about? Hecouldn't look worse if Noakes was his landlord and he couldn't pay therent. And upon my word, Noakes has cheek enough for two. I saw himprodding the cattle the other day as if he owned 'em, or would like to.What do you think about it?"

"Eh? about Noakes? I wasn't thinking of him," said Templeton. "I waswondering whether we couldn't do something to help save the old man'scrops."

"Well, old chap, if you can invent rain----"

"Don't be an ass. Of course I can't. But I don't see why we shouldn'tirrigate, as they do in India."

"We haven't got an Indus, and the river down there is too far away, andbelow this level. You can't make water run up-hill."

"But there's the brook just at the edge of the field, behind that ridge.All we've to do is to divert it."

"My good man, it's miles below the top of the ridge. Besides, there'snot much water at the best."

"There's enough. We should have to build a dam, of course. Then thewater would collect till it rose to the height of the ridge and flowedover, and we could carry it over the fields through small drains. Yousee, the stream runs straight to the sea; there are no fishing rights toconsider, and it's not used for mills or anything of that sort."

"A jolly back-aching job, digging drains and what not. No chance of arag. Still, the idea's good enough, and I'd like to see old Trenchardmore cheerful. You had better see what he says about it."

The farmer was so much preoccupied with his gloomy thoughts that hescarcely appreciated at first the nature of the service which Templetonoffered to render. This, as Eves pointed out afterwards, was partly dueto Templeton's manner of broaching the subject.

"Your jaw about irrigation and the Punjab was enough to put him off it,"said Eves, who was nothing if not frank. "Of course, the old countrymandidn't understand; he understood right enough when I chipped in. There'snothing like what old Dicky Bird, when you do a rotten construe, calls_sancta simplicitas_."

Between them they managed to explain the idea to Mr. Trenchard, and towin his assent. Indeed, the chance of saving his crops had a magicaleffect on his spirits.

"It do mean a mighty deal to me," he said; "more'n you've any rightnotion of. I wish 'ee success, that I do."

They started work on the following morning. From the rocky banks of thestream they rolled down a number of stones and boulders and piled themin the channel to the height of the ridge, forming two adjacent sides ofa square. Then up stream they cut a quantity of brushwood, which, beingset afloat, was carried by the water against the piled-up stones. Thisoccupied them the whole day, and they left for the next the finaloperation--the digging of earth to stop up the interstices through whichthe water still flowed away, and the carrying of it in wheelbarrows toits dumping places.

It was while they were digging that Lieutenant Cradock arrived tointerrogate them about the conscientious objections of Nahum Noakes.About half an hour after his departure Nahum's father appeared on thescene, breathless from hurrying up the hill from the village. He hadpumped Constable Haylock, who was a simple soul, and had learnt enoughabout the recent interview to feel a gnawing anxiety as to the fate ofhis beloved Nahum. He was hatless, and wore his apron, with which hewiped the shining dew from his face as he stood watching the diggers.

"Marnen, gen'l'men," he said, presently, in the tone of one who would bea friend. "'Tis warm work 'ee be at, surely."

"A warm day, Mr. Noakes," said Templeton, resting on his spade. Eveswent on digging.

"Ay, sure, 'tis warm for the time o' year, so 'tis. Vallyble work; ifthere be one thing I do admire, 'tis to see young gen'l'men go forthunto their labour until the evening, as the Book says--earning theirbread with the sweat of their brow. Ah, 'tis a true word."

Templeton was too modest to acknowledge this compliment. Eves went ondigging. Mr. Noakes hemmed a little, and stroked his beard.

"Purticler such young gen'l'men as you be," he went on, "as hev gonedeep into book learning and gives yer nights and days to high matters.That there finology, now; that be a very deep subjeck--very deep indeed;wonderful, I call it, to read into the heart through the head. Nobody'ud never hev thought 'twere possible. And so correck, too; my boyNahum, as peaceful as a lamb--you was right about that there bump, sir."

"He certainly hasn't got the bump of combativeness," said Templeton;"but----"

"Ah, yes, to be sure; he was a trifle overtaken with yer friend's joke,as any young feller might be; but I told un 'twas just a bit o' juvenilehigh spirits, and so he oughter hev took it. 'Let not the sun go downupon yer wrath,' says I, and bless 'ee, he smiled like a cherub nextday, he did. That there bump be a good size on soldiers' heads, now? Iwarrant that young officer man as I seed down in village has a big un."

"I really didn't think to look, Mr. Noakes," said Templeton, patiently.

"Only think o' that, now, and I felt in my innards he'd come up alonga-purpose. You didn't say nought o' finology, then?"

"Well, it was mentioned--just mentioned."

"And Mr. Templeton assured Lieutenant Cradock that your son hadn't theslightest prominence in that part of the skull," Eves broke in. "Infact, it's the other way about."

"Wonderful ways o' Providence!" said Mr. Noakes, rubbing his handstogether and smiling happily.

"But I'm bound to say----" Templeton began.

"Come on, Bob; shovel in, or we'll never get done," Eves interrupted."There's enough stuff dug; let's cart it down. We're trying anexperiment in irrigation, Mr. Noakes."

"Ah! irrigation. It needs a dry soil, to be sure; it'll grow wellhere--very well indeed."

Eves smothered a laugh, and let Templeton explain. The explanation,strangely enough, brought a shadow upon Mr. Noakes's face. It darkenedas he watched the dumping of the earth upon the dam. He was silent; hismouth hard

ened; and after a few more minutes he shambled away.

"I'm afraid we've given him a wrong impression," said Templeton,anxiously.

"Well, he shouldn't be sly. Besides, if he's ass enough to think'finology' will go down with the tribunal, that's his look-out."

They worked hard through the rest of the day, and by tea-time the waterhad begun to trickle over the ridge in many little rills. It seemed,indeed, that there would be no necessity to dig the channels of whichTempleton had spoken, the slope of the ground and the natural fan-likespreading of the streams promising that in due time the whole fieldwould be thoroughly watered. Tired, but well pleased with the successof their experiment, they returned to the farmhouse.

Mr. Trenchard had been absent all the afternoon. At tea they told himwhat they had done, and he cheerfully assented to their suggestion thathe should go with them to the ridge and see for himself their irrigationworks.

It was dusk when they started. The ridge was at an outlying part of thefarm, and as they strolled across the intervening fields Eves suddenlyexclaimed:

"What's that?"

Some hundreds of yards ahead, a whitish object, not distinguishable inthe dusk, was moving apparently along the top of the ridge. In a fewseconds it disappeared.

"That was one of they rabbits after my turmuts, I reckon," said thefarmer. "Terrible mischeevious little mortals they be."

"I say, Bob," cried Eves, "we might have a rabbit hunt one of thesedays."

"We've a lot of other things on hand," said Templeton, dubiously. "Yousee, there's the tar entanglement, and----"

"There it is again," said Eves, pointing towards a hedge some distanceto the left beyond the ridge. "Rabbits don't live in hedges, do they,Mr. Trenchard?"

"Not as a general rule," replied the farmer, cautiously; "but there's nosaying what they'll be doing. He's gone again; we've frighted himaway."

"Well, here you see what we've done," said Templeton. "The dam thereholds back the stream, the water is forced to rise, and it's now findingits way over the ridge in many little rivulets which I daresay byto-morrow morning will have flowed right over the field."

"Well to be sure!" said Mr. Trenchard. "Now that's what I call adownright clever bit of inventing. And to think that there stream hevbeen a-running along there all the days of my life, and I never seed nouse for un! 'Twill be the saving of my roots, young gen'l'men, and I'mmuch beholden to 'ee."

It was as though a load had been lifted from the old man's mind. He wasmore cheerful that night than his guests had yet seen him, and waseasily persuaded to join them and his wife in a rubber of whist.

Early hours were the rule at the farm. By nine everybody was in bed butthe two strangers. They were always the last to retire. About ten theyhad just undressed. It was a hot, sultry night; the bedroom, low-pitchedand heavily raftered, was stuffy; and Eves, after blowing out thecandle, pulled up the blind and leant out of the window to get a breathof what air there was. The sky was slightly misty, and the moon, in itslast quarter, threw a subdued radiance upon the country-side.

"By George!" exclaimed Eves, suddenly; "there's that white thing again."

"What does it matter?" said Templeton, who was getting into bed. "We'vegot to be up early; come on."

"Come and look here, you owl. That's no rabbit. It's bobbing up anddown, just where the dam is. I'll be shot if I don't believe some one'sinterfering with it."

This suggestion brought Templeton to the window at once. Side by sidethey gazed out towards the ridge.

"This is serious," said Templeton. "If it really is any one interferingwith our work----"

"We'll nip him in the bud. Come on; don't wait to dress; it's quitewarm. Get into your slippers. We'll go out of the back door withoutwaking the Trenchards and investigate."

Two minutes later they were stealing along under cover of the hedge thatskirted the field to be irrigated. Arriving at the ridge some distanceabove the dam they turned to the left, and bending double crept towardsthe scene of their toil. There, rising erect, they saw Mr. Noakes up tohis thighs in the stream, hard at work pulling away stones and earthfrom the dam.

The water was already gurgling through.

"Hi there! What the dickens are you up to?" Templeton cried.

The man turned with a start, and faced them. He appeared to beundecided what to do.

"What are you about?" repeated Templeton, indignantly. "What right haveyou to destroy our dam?"

"What right!" said the man, indignant in his turn. He was still in thewater, and, leaning back against the dam, he faced the lads in the mistymoonlight. "What right hev you two young fellers, strangers in theparish, to play yer mischeevious pranks here? 'Tis against the law tointerfere wi' the waterways o' the nation, and the Polstead folk hevtheir rights, and they'll stick to 'em. Ay, and I hev my rights, too,and I'm a known man in the parish. This here stream purvides me wi'washing water, and to-morrow's washing day. You dam up my water; Ican't wash; that's where the right do come in."

"My dear sir," said Eves, gravely, "however much you want washing, andhowever much it is to the interest of your neighbours that you shouldwash, the interests of our food supply, you must admit as a patrioticman, are more important. Wash by all means--to-morrow, when the dam,having done its work, will no doubt be removed. For my part, I have adistinct bias in favour of cleanliness. If a man can't be decent inother things, let him at least be clean. There was young Barker, now, awretched little scug who wore his hair long, and always had a high-watermark round his neck. My friend Templeton, of whose ingenuity you haveseen proofs, had an excellent invention for an automatic hair-cutter.But I am wandering from the point, which was, in a word, how to be happythough clean----"

Eves was becoming breathless. He wondered whether he could hold out.Templeton gazed at him with astonishment; as for Mr. Noakes, he lookedangry, puzzled, utterly at sea. Once or twice during Eves's oratoricalperformance he opened his mouth to speak, but Eves fixed him with hiseyes, and held up a warning hand, and overwhelmed him with hisvolubility.

"Yes, how to be happy though clean," Eves went on; "there's a text foryou. Cleanliness is an acquired taste, like smoking. The mewling infant,with soapsuds in his eyes, rages like the heathen. The schoolboy,panting from his first immersion--my hat!"

The expected had happened. During Eves's harangue, the water had beeneating away the pile of soil and rubbish which had been loosened by Mr.Noakes's exertions. Without warning, the dam against which the man wasleaning gave way. He fell backward; there was a swirl and a flurry, andMr. Noakes, carried off his feet by the rush of water, was rolled downstream. His new soft straw hat, which had betrayed him, floated onahead.

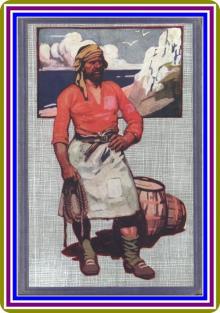

Templeton sprang over the ridge and hastened to Mr. Noakes's assistance.For the moment Eves was incapacitated by laughter. Fortunately thestream was not deep, and after the first spate it flowed on with lessturbulence. Templeton gripped the unhappy man by the collar, and hauledhim up after he had been tumbled a few yards. Breathless, he stood apitiable object in his frock-coat and baggy trousers, his lank hairshedding cascades.

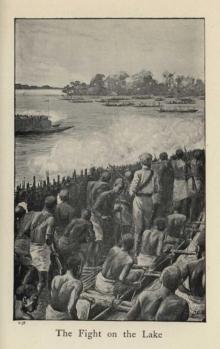

"TEMPLETON GRIPPED THE UNHAPPY MAN BY THE COLLAR, ANDHAULED HIM UP."]

"A most unfortunate accident," said Templeton. "You see, by removingsome of the stones----"

"Mr. Noakes, your hat, I believe," interposed Eves, handing him thesodden, shapeless object which he had retrieved from the stream. Mr.Noakes snatched it from him, turned away, and started downhill. Never aword had he said; but there was a world of malevolence in his eye.

"We had better get back and dress," said Templeton.

"What on earth for?"

"Well, we can hardly repair the dam in our pyjamas."

Eves laughed.

"You're a priceless old fathead," he said. "Repairs must wait till themorning. I can never do any work after a rag."

"A rag! But it was a pure accident, due to the idiot's ownmeddlesomeness."

"Most true; but it wouldn't have happened if I hadn't kep

t his attentionfixed by the longest spell of spouting I ever did in my life. It was aripping rag, old man, and now we'll toddle back to bed. The one thingthat beats me is, what's his motive? He'd hardly take the trouble tosmash our dam just to get even with us, would he? That's a kid's trick.There's something very fishy about old Noakes."

Kobo: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War

Kobo: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War Frank Forester: A Story of the Dardanelles

Frank Forester: A Story of the Dardanelles Wizard Will, the Wonder Worker

Wizard Will, the Wonder Worker With Marlborough to Malplaquet: A Story of the Reign of Queen Anne

With Marlborough to Malplaquet: A Story of the Reign of Queen Anne The Dogs of Boytown

The Dogs of Boytown Brown of Moukden: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War

Brown of Moukden: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War Detectives, Inc.: A Mystery Story for Boys

Detectives, Inc.: A Mystery Story for Boys Bright Ideas: A Record of Invention and Misinvention

Bright Ideas: A Record of Invention and Misinvention Lost in the Cañon

Lost in the Cañon The Rival Campers Afloat; or, The Prize Yacht Viking

The Rival Campers Afloat; or, The Prize Yacht Viking The Flying Boat: A Story of Adventure and Misadventure

The Flying Boat: A Story of Adventure and Misadventure The Flying Reporter

The Flying Reporter Jack Hardy: A Story of English Smugglers in the Days of Napoleon

Jack Hardy: A Story of English Smugglers in the Days of Napoleon No Man's Island

No Man's Island The Motor Scout: A Story of Adventure in South America

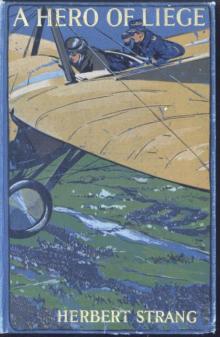

The Motor Scout: A Story of Adventure in South America A Hero of Liége: A Story of the Great War

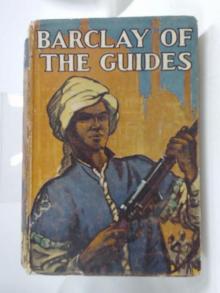

A Hero of Liége: A Story of the Great War Barclay of the Guides

Barclay of the Guides Carry On! A Story of the Fight for Bagdad

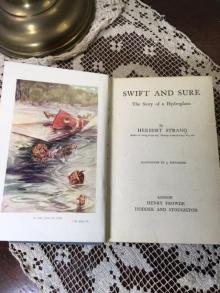

Carry On! A Story of the Fight for Bagdad Swift and Sure: The Story of a Hydroplane

Swift and Sure: The Story of a Hydroplane The Air Patrol: A Story of the North-west Frontier

The Air Patrol: A Story of the North-west Frontier Boys of the Light Brigade: A Story of Spain and the Peninsular War

Boys of the Light Brigade: A Story of Spain and the Peninsular War The Rival Campers; Or, The Adventures of Henry Burns

The Rival Campers; Or, The Adventures of Henry Burns Palm Tree Island

Palm Tree Island The Friends; or, The Triumph of Innocence over False Charges

The Friends; or, The Triumph of Innocence over False Charges Maggie's Wish

Maggie's Wish Tom Burnaby: A Story of Uganda and the Great Congo Forest

Tom Burnaby: A Story of Uganda and the Great Congo Forest Settlers and Scouts: A Tale of the African Highlands

Settlers and Scouts: A Tale of the African Highlands In Clive's Command: A Story of the Fight for India

In Clive's Command: A Story of the Fight for India Samba: A Story of the Rubber Slaves of the Congo

Samba: A Story of the Rubber Slaves of the Congo The Auto Boys' Quest

The Auto Boys' Quest Tom Willoughby's Scouts: A Story of the War in German East Africa

Tom Willoughby's Scouts: A Story of the War in German East Africa The Adventures of Harry Rochester: A Tale of the Days of Marlborough and Eugene

The Adventures of Harry Rochester: A Tale of the Days of Marlborough and Eugene Fighting with French: A Tale of the New Army

Fighting with French: A Tale of the New Army Round the World in Seven Days

Round the World in Seven Days The Adventures of Dick Trevanion: A Story of Eighteen Hundred and Four

The Adventures of Dick Trevanion: A Story of Eighteen Hundred and Four