- Home

- Herbert Strang

Brown of Moukden: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War Page 5

Brown of Moukden: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War Read online

Page 5

*CHAPTER IV*

*The Great Siberian Railway*

Duty and Inclination--A Domiciliary Visit--Monsieur Brin Protests--AReminder--The Ombeloke--Quandary--Salvage--A Fortune in Soles--FellowPassengers--From a Carriage Window--A Further Search--At the SungariBridge--Off the Line--The Compradore's Brother--Consultation--ABargain--The Terms--The Last Load--In a Horse-box

Jack had rage in his heart as he walked back to the city. He was angryand indignant, but even more alarmed. The general had told him little:was that little the truth? What did he mean by "deported"? If Mr. Brownhad really been put across the frontier, why should the general haverefused to say by what route he had travelled? Jack feared that therehad been foul play, and his anxiety was none the less because he couldnot imagine what form the foul play had taken.

His own position was awkward. He was homeless; in a few hours he was tobe packed like a bundle of goods into a train and carried away againsthis will. His father might have preceded him to Europe; on the otherhand, he might not. Was he to leave Moukden thus, in uncertainty as tohis father's fate?

Thus perplexed and troubled in mind, he walked back to his house. Atthe door he found Monsieur Brin in a state of desperation at hisinability to make head or tail of the compradore's pidgin English.

"Ha, my friend!" he exclaimed, "I am glad to see you; I must know theworst; I come in haste, but the Chinese man speaks a language ofmonkeys; I understand it not. Tell me what is arrived."

"I have seen General Bekovitch," replied Jack. "He told me almostnothing. My father has been deported--for betraying secrets to theJapanese, if you please! Did you ever hear of anything so ridiculous,so preposterous!"

"But that is all right. O.K. Deported! Mr. Brown is the happy man.It would please me to be deported also. He goes back to Europe: that Icould accompany him!"

"But that is the point. Has he gone back to Europe? The general wouldnot tell me. And he is packing me off too! I have to leave byto-night's train for Harbin, or he will put me under arrest."

"He! That is a scandal. I will expose it. I will write it all to myredacteur. Ah! But I ask myself, will the redacteur publish my letter?France is allied to Russia. A French publicist has to consider notsolely his own persuasions, but his duty to his country. I reflect: itwill be best actually to write nothing. But if, my friend, there needsmoney, demand me; I can furnish hundred, hundred and fifty roubles: itwill be to me a pleasure."

"Many thanks, Monsieur! I do not think I shall need your assistance. Itold the general I shall appeal to our government. Unluckily we have noconsul here; the nearest, I suppose, is at Shanghai; and being sent offto Harbin, I don't know when I shall have an opportunity ofcommunicating with our authorities."

"Truly, it is a difficult situation. And your goods here: what willthey become?"

"They'll be confiscated, I suppose. As you see, I am locked out.Luckily we have nothing of any great value. My father sent off inadvance all that he wished to keep, and they can't touch his account atthe Hong-Kong and Shanghai bank."

He said nothing about the securities in Hi Lo's possession, not from anywant of faith in the Frenchman's good-will, but not entirely trustinghis discretion.

"They have no right to lock me out," continued Jack. "And as GeneralBekovitch said he'd send me a pass for the train, he must suppose he'llfind me here. So if Mr. Hi will put his shoulder to the door, I thinkwe'll force the lock and see what they have been doing."

The stalwart compradore made short work of the fastenings. Accompaniedby Monsieur Brin and the Chinaman, Jack entered his father's house.There were manifest signs of ransacking. The floor of the office wasstrewn with papers; in the dining-room the drawers had been emptied; anda large oaken press, a fine specimen of Chinese cabinet-making on whichMr. Brown set much store, had been forced open. They were contemplatingthe dismal scene when Hi Lo came running in.

"Masta," he said hurriedly, "thlee fo' piecee Lusski walkee chop-chopthis-side."

A Search Party]

A few moments later the house was entered by four Siberian infantrymen,headed by a lieutenant and accompanied by a tall, fair, hook-nosed man,at the sight of whom Jack started. A light flashed upon him. AntonSowinski was the Russian Pole who had been doing his best to ruin Mr.Brown's business, and had so bitterly resented Mr. Brown's successes.It was he, too, who had instigated the charge trumped up against WangShih in revenge for a business defeat. Was it unlikely that Sowinskihad been the agent in this other trumped-up charge of espionage? Ifnot, what was his business now?

"I have come," said the lieutenant, "to bring you the pass promised byGeneral Bekovitch. Here it is."

He drew a large unsealed envelope from his pocket, and took from it apaper which he proceeded to read. It stipulated that Mr. John Brown,junior, was to leave Moukden by the train for Harbin at 8 p.m., en routefor Europe. Replacing it in the envelope, the officer laid this upon thetable and said:

"I regret, Monsieur, that I have a disagreeable duty to perform. I amordered to search the house and everybody in it. Mr. Brown is known tohave been in possession of certain vouchers which are now forfeit to mygovernment. They could not be found when he was arrested; the conclusionis that they are in your possession. I must ask you to turn out yourpockets."

"I have no papers," said Jack, "and I protest."

"I am sorry. I have my orders to carry out. Resistance is useless."

"Oh! I shall not resist. Search away."

The lieutenant had already posted a soldier at the back entrance, andhad sent another man to bring into the room anyone whom he might find onthe premises. As Jack was being searched, Hi Lo was brought in; he hadslipped away when the Russians entered. Jack hoped that the boy had hadtime to hide the papers, for though the amount they represented wassmall in comparison with his father's total fortune, it was yetconsiderable in itself, and he was anxious to save it, not merely forits own sake, but because without it he would have no means of carryingthrough a plan he had already dimly determined on. Hi Lo's face wasvoid of all expression. There were now in the room, besides theRussians, Jack himself, Monsieur Brin, the compradore, and his son. Thedoor was locked.

Jack was searched from top to toe. Nothing was found on him saveletters of no importance. The compradore and Hi Lo were examined inturn; they submitted meekly, and Jack almost betrayed his relief when hesaw that the papers had not been discovered on the boy. Then theofficer turned to Monsieur Brin, glancing at the red band on his arm.

"But I am a Frenchman," exclaimed the angry correspondent. "Why do yousearch me? I have nothing. I know nothing."

"I find you in Mr. Brown's house. I have orders to search everybody. Ihope you will make no difficulty, Monsieur."

"Difficulty! It is you that make difficulty. It is an insult, anindignity. I am an ally; peste! for what good to be an ally if I amthus treated as an enemy! But I do not resist; no, I resign myself.From no one but an ally would I endure such an indignity."

"I am exceedingly sorry, Monsieur. General Bekovitch, in giving orders,of course did not contemplate for a moment the case of a Frenchcorrespondent being present; but my instructions are positive. I haveno choice but to carry them out."

"Well, I protest still once more. I will make the French nation knowthe price they pay for this so agreeable alliance."

Monsieur Brin was searched. No papers were found on him except hispocket-book, a lady's photograph, and several letters, which the officerglanced through, the Frenchman fuming with impatience and indignation.At the conclusion of the search the lieutenant threw a meaning glance atSowinski, whose attitude throughout had convinced Jack of thecorrectness of his surmise. The Pole's presence was in itself asufficient proof of his personal interest in Mr. Brown's fate. An hourwas spent in making a further examination of the scattered papers;nothing incriminating being found, the lieutenant gave his men the orderto march. At the last moment he glanced at the enve

lope on the table.

"Take care of it, Monsieur," he said; "it would be awkward for you if itwere lost."

When the party had gone, Monsieur Brin fairly exploded with wrath.English was too slow for him; a rapid torrent of French came from hisquivering lips. But Jack's attention was diverted from the Frenchman bythe strange antics of Hi Lo, who was dancing round his father, his facebeaming with delight.

"You hid the papers?" said Jack. "You are a good boy. Where are they?"

The boy pointed to the envelope on the table.

"What do you mean?"

"Masta, look-see. Masta, look-see."

Jack lifted the envelope. The boy's glee puzzled him. Opening it, hetook out the Russian pass, and with it half a dozen thin slips of paperwritten upon in Russian and French. He could hardly believe his eyes.They were the very papers for which the officer had sought so diligentlybut in vain.

"How is this? What does it mean?" he said in blank amazement.

"Hai-yah! Velly bad Lusski man look-see Masta; allo piecee bad manlook-see all-same; no can tinkee Hi Lo plenty smart inside. Hai-yah!Allo piecee Lusski man look-see that-side; my belongey this-side, makeeno bobbely; cleep-cleep 'long-side table; my hab papers allo lightee:ch'hoy! he belong-ey chop-chop inside ombeloke; Lusski no savvy nuffin'bout nuffin, galaw!"

Jack burst into a roar of laughter, and translated the boy's pidgin tothe bewildered Frenchman. While the Russians were intent on searchingJack, and their backs were towards Hi Lo, the boy, knowing that his turnmust come, seized the opportunity to slip the precious papers into theunclosed envelope on the table. Monsieur Brin flung up his hands andbegan to pirouette, then stopped to laugh, and held his shaking sides.

"Hi! hi! admirable! Excellentissime! Bravo! bravo! Ma foi! Comme ilest adroit! Comme il est spirituel! Ho! ho! Tiens! Le gars merite uneforte recompense. Voila!"

In his excess of enthusiasm he took a silver dollar from his pocket,spun it, and handed it to Hi Lo. The boy was sober in an instant. Hegravely handed the coin back.

"No wantchee Fa-lan-sai man he dollar," he said.

Brin looked to Jack for an explanation.

"He is much obliged, but would rather not. You made a little mistake,Monsieur. You can't offend a Chinaman of this sort more than byoffering him money. He is, indeed, a clever little chap. I'll takecare he doesn't go unrewarded."

"Ha! That is another point for my chapter on the characteristics of theChinese. But now, my friend, what will you do?"

"Really, Monsieur, I don't know. I must talk it over with thecompradore."

"Very well then, I leave you. I go to write notes of this mostinteresting episode. I begin to enjoy war correspondence. You go ateight? I will be at the station to say adieu."

Jack spent more than an hour in serious consultation with Hi An, thecompradore, a man of forty, who had served his father for nearly twentyyears, and was heart and soul devoted to his interests. There was noquestion but that Jack must leave Moukden that night, and Hi An advisedhim to go straight to Moscow and take the first opportunity ofcommunicating with the British Foreign Office. Meanwhile the compradorehimself would do what he could to trace the whereabouts of his master.But this course Jack was very unwilling to adopt. In the first place,he had his father's instructions to realize the securities, so cleverlysaved by Hi Lo. Then there was the consignment of flour which he hopedmight run the Japanese blockade and come safe to harbour at Vladivostok.If it should arrive it would be worth a large sum of money, and Jack wasnot disposed to yield that a spoil to the Russians. Last and mostimportant consideration, he was oppressed by the mystery of his father'sfate. With the likelihood of innumerable delays on the congestedrailway, he might be three weeks or a month reaching Moscow; he foresawdifficulties in inducing the Foreign Office to move in a case wherethere was so little to go upon; and, above all, it was unendurable tothink that his father might, for all he knew, be still near at hand, indanger and distress.

He was already determined, then, that, leave Moukden if he must, hewould not leave Manchuria. But what could he do to secure his objectsand his own safety? He wondered whether the news of his father's arresthad been telegraphed to Harbin and Vladivostok. That was unlikely, hethought, for two reasons. It was well known that Mr. Brown had beenwinding up his business; the Russian authorities, unless speciallyinformed, would not suppose that there was any plunder to be got apartfrom what was found at Moukden. And the telegraph had been for monthspast very much overworked, what with the heavy railway traffic and theconstant messages flashing to and fro between the principal depots inManchuria and between Manchuria and St. Petersburg. It was thereforeunlikely that the enforced departure of a Moukden merchant would beconsidered of sufficient importance to communicate. If this reasoningwas correct, and Jack could contrive to reach Vladivostok before thenews filtered through, he might save the remnants of his father'sproperty, and turn the vouchers into negotiable securities. He wouldthen find himself in possession of considerable funds, which he mightuse if necessary in tracking his father.

The first thing was to get to Vladivostok. The pass stipulated that heshould go through Harbin over the Siberian railway to Moscow. To reachVladivostok he must change trains at Harbin, and by that very factbecome a fugitive and an outlaw. Apparently General Bekovitch did notintend to send him north under an escort; it probably never occurred tohim that with his father deported, his home broken up, Jack would makean effort, in face of the definite order to quit the country, to remain.But though no escort was provided, he would undoubtedly be watched; andto slip away at Harbin in a direction the opposite of that intendedpromised to be a matter of considerable difficulty and danger.

The compradore shook his head when Jack explained what he had in hismind. Then, finding that his young master was determined, he did notattempt to dissuade him, but set himself in earnest to talk over waysand means. He had a brother in Harbin, a grain merchant, who haddealings with the Russians. This man might be able to give Jackinformation and assistance, and to him the compradore wrote a short noteof introduction. The next thing was to provide for the safety of theRussian vouchers. Jack might be searched again _en route_, and it wastherefore inadvisable to carry them in his pocket. He pondered for atime without finding any solution of the difficulty. He was sittingwith crossed legs, his hands clasping his knee, his eyes cast down.Studying the heavy thick-soled boot he wore in summer, under stress ofManchurian mud, he suddenly bethought himself.

"You can turn your hand to most things, Mr. Hi; do you think you couldsplit the sole of one of my boots and put it together again?"

"Of course, sir."

"That's the very thing, then. No one would ever think of taking my bootto pieces."

Hi An very quickly and deftly performed the necessary operation.Between the two parts of the split sole Jack placed the vouchers andletter of introduction; then the compradore neatly stuck them togetheragain. He produced a roll of rouble notes, enough to pay preliminaryexpenses and leave a margin for emergencies.

"There, Master," he said. "I have done all I can."

"You're a good fellow. I must trust to the chapter of accidents for therest. I may never see you again, Mr. Hi. If I come to grief, you willdo what you can to find my father?"

"I will, Master, if I have to trudge on foot all the way to Pekin to askhelp of the Son of Heaven himself."

Some minutes before eight o'clock Jack, by virtue of his pass, wasadmitted without a ticket to the platform at which the train for Harbinwas drawn up. He had been compelled to take his farewell of MonsieurBrin, the compradore, and Hi Lo outside, much to the Frenchman'sindignation. The line was very badly managed; the officials weresoldiers, with no technical acquaintance with railway management.Trains were despatched from Moukden to Harbin, and from Harbin toMoukden, at any time that suited the officials at either end, withoutprearrangement, sometimes even without communication between thestations. On this particular train there was no distinction of classes,

and Jack found himself one of some forty passengers packed into acarriage built for thirty. The company was exceedingly mixed. Russianofficers were cheek by jowl with Chinese merchants; a huge long-beardedRussian pope was wedged between a German commercial traveller and aSister with the red cross on her arm; at one end was a group ofchattering Greek camp-followers, who brought out a filthy pack of cardslong before the train started, and began a game of makao, whichcontinued, with intervals for squabbling and refreshment, all the way toHarbin. Jack made himself as comfortable as he could in a corner, andprepared to sleep if the close proximity of his fellow-passengers andthe stuffiness of the air allowed.

It was past nine o'clock before the train steamed out. Punctuality is avirtue non-existent on the Siberian railway. The journey taxed Jack'spatience to the utmost. The line is single, doubled at intervals of fiveversts to allow of the passage of trains in opposite directions. Thetrain was constantly being shunted into sidings, remaining sometimes forhours, no one could tell why; and one of the most annoying features ofthe constant stoppages was that the train, after running through astation where the passengers would have been glad to obtainrefreshments, would come to a stand several versts beyond, where theyhad nothing to do but kick their heels and look disconsolately out onthe country. On one of the sidings stood a goods train, two trucks ofwhich were loaded with a large gun; it had no doubt been injured by aJapanese shell, and was being returned to arsenal for repair. Inanother train Jack noticed a truck crowded with poor wretches whoappeared to be chained together--misdemeanants from the army, hesurmised, on their way to one of the penal settlements in Siberia. Atshort intervals appeared the little brick huts of the soldiers guardingthe line, and occasionally a group of three or four of thosegreen-coated guards might be seen riding along at the foot of theembankment on their stout Mongol ponies.

Jack had travelled many times along the line, but not recently, and hewas greatly interested in the amazing developments which it hadundergone. New buildings of brick seemed to have sprung up likemushrooms along its course. Where formerly had been spacious fields ofkowliang--the long-stalked millet of the country--with Chinese fangtzesfew and far between, there were now wide bare stretches upon whichRussian industry was erecting storehouses, engine-sheds, tile-coveredresidences for the officials. Some thirty-five miles from Moukden isTieling, which, when Jack's train passed through at three o'clock in themorning--having taken just six hours to run that distance--seemed to benothing but a collection of scaffolding, with Chinese bricklayersalready at work, trowel in hand. Between Tieling and Harbin stretchesan immense plain, fertile for the most part, and hitherto left almostunspoiled. Nowhere does the line pass through a Chinese village; thesewere purposely avoided by the Russian engineers from motives of policy,and in deference to native susceptibilities. They are for the most partout of sight from the railway. All that can be seen is, on the right,the broad rutty mandarin highway; on the left, a narrower road edginginterminable fields of kowliang. There are few stations between Moukdenand Harbin: at two, Tieling and Kai-chuang, the Russians had establishedtheir base hospitals.

Hour after hour passed. Jack whiled away a good part of the time bywhittling sticks with his penknife, somewhat to the amusement of theRussian army doctor who sat next to him, and who did not appear tonotice that the sticks were shaped to a definite size, and that, afterseveral had been thrown away, two or three were placed in Jack's pocket.Many times the train was halted at a doubling to allow a troop train topass, filled with Russian soldiers on the way to the front, shouting,singing, in the highest spirits. At one point an empty Red Cross trainstood on a siding, having emptied its freight of wounded men at one ofthe hospitals.

During one of the stoppages the belaced official who acted as guardpolitely requested Jack to step into the station-master's office, wherehe was searched by one of the soldiers. He was thus left in no doubtthat he was under surveillance, and when he got back to his carriage hefound that his bag had been opened. He congratulated himself on hisforethought in concealing his papers so effectually in his boot.

At the moment of saying good-bye the compradore had given him a piece ofnews that made him anxious to complete his journey. A Chinese employedat the station had told him that Anton Sowinski had booked a seat by thenext day's train. It was by no means impossible that this train, if ithappened to carry any important passengers, would overtake and pass thefirst somewhere on the line. The Pole was likely to spread the news ofMr. Brown's arrest, and if he should succeed in getting to Vladivostokbefore Jack the game would certainly be up.

At length, about forty-five hours after leaving Moukden, someone saidthat Harbin was in sight, and there was instantly a movement and bustleamong the passengers.

"Keep your seat," said the doctor to Jack with a smile.

"Thanks! I know," said Jack with an answering smile.

The train slowed down, then stopped at the southern end of the bridgeover the Sungari river. It was as though the engine were parleying withthe sentry. On the right rose the barracks of the frontier guards,surrounded by a loopholed wall. At the bridge end were two guns framedin sand-bags, and watched by two sentinels. Across the river, above andbelow the bridge, an immense boom prevented traffic either up or down.While the train halted, an official came along the carriages, fastenedall the windows, locked all the doors; to open them before the bridgewas crossed entailed a heavy penalty. When all the passengers were thussecured, and there was no chance of any Japanese spy throwing a bomb onto the bridge, the train moved slowly on, passed more guns at thefarther end, and came to rest at the spacious station in the Russianquarter of the town.

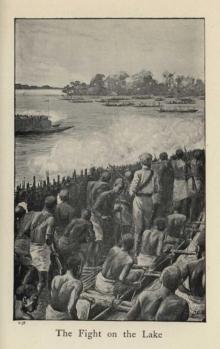

Map of Manchuria and part of Siberia]

A train from Vladivostok was expected during the afternoon, and thecomposite train would leave for the west at nine o'clock. Jack went outwith the majority of the passengers into the buffet, which is one of theadmirable features of the Russian railway system, and ordered a goodmeal. Then he looked over some illustrated papers, making no attempt toleave the station, having noticed that he was still watched by one ofthe train attendants. Time hung heavily; he took a nap on one of theseats, and when he awoke found that the Vladivostok train had arrived,and the night train for the west was being made up. Strolling out withhis bag, he showed his pass to an official, and by means of a liberaltip secured a sleeping compartment to himself. He explained with manyyawns that, being tired out, he intended to turn in as soon as the trainstarted, and asked the man to arrange his bed and lock him in. Theattendant complied, and a few minutes later Jack noticed him inconversation with the man under whose watchful eyes he had been all day.The latter appeared satisfied and went away.

The train was late in starting; a high personage, it seemed, wasexpected. Jack stood for some minutes at the door, watching the variedcrowd on the platform Suddenly he heard cheers; the high personage hadno doubt arrived. A warning bell rang; the officials called to thepassengers to take their seats. Jack took off his coat in full viewfrom the platform, then drew the curtain, opened his bag, and took fromit, not a night costume, but a brush, a comb, and a collar. Then heturned off the light.

But instead of throwing himself on his bed, he went to the opposite doorof the compartment and tried it; as he expected, it was locked. He puton his coat, crammed into the pockets the articles he had taken from hisbag, and from his vest pocket took one of the sticks he had beenwhittling on the way from Moukden. Leaning out of the window, heinserted it in the lock. The train was just beginning to move. Wouldthis extemporized key serve? He turned it; the lock clicked; and thenext moment he was on the foot-board. Silently closing the door hedropped to the ground, and ran alongside the moving train, stumbling andtripping over the rugged ballast. The pace quickened and the trainbegan to distance him; but he made all the speed he could, and by thetime the last carriage had passed him he found, to his relief, that hewas beyond the station and in darkness. Dodging behind an engine-shed heclambered over a fence, left the railway, and set off

to find the houseof the compradore's brother.

He had taken the precaution, before starting, to obtain very explicitdirections, in order to save time, and to avoid the risk involved inasking questions. The Chinese part of the town is some three miles fromthe station, on lower ground near the river. The streets wereabominably filthy; and by the time Jack reached the priestan ormerchants' quarters he felt sadly in need of a bath. By following thecompradore's instructions he found the grain store of which he was insearch, though with some trouble. All the business premises in theneighbourhood were closed for the night; there were few people in thestreets: the Chinaman as a rule barricades himself in his house atnightfall. Making sure by peering at the sign that he had come to theright house, Jack gently knocked at the door. It was opened by aChinaman, whom Jack recognized by the light of the oil-lamp he carriedas the compradore's brother.

"I am from Moukden, Mr. Hi," said Jack, "and have a note from yourbrother Mr. Hi An."

"Come in," said the Chinaman at once, without any indication ofsurprise. Jack pulled off his dirty boots and followed him to a littleback shop, where he had evidently just been engaged in brewing tea. Heasked Jack to sit down, poured him out a dish of tea, and then waitedwith oriental patience to hear what his visitor had to say. Prising openthe sole of one of his boots, Jack drew out the compradore's note. Itbore only three Chinese characters, and said merely that Hi An wishedhis brother to give all possible assistance to the bearer. The Chinamanlooked up with an expression of grave polite curiosity and still waited.

The compradore having said that his brother could be thoroughly trusted,Jack explained to him, as simply and clearly as he could, thecircumstances that had brought him to Harbin, and the object of hisvisit. When the Chinaman had heard the story, and learnt what wasexpected of him, he looked somewhat scared. He said that the Russianswould inflict the most terrible punishments upon him if they discoveredthat he had sheltered and assisted a fugitive. He spoke of his terrorof the Russian knout. But the Englishman might command him to do whathe could. Had he not himself received benefits from Mr. Brown? Fiveyears ago, he said, when he was on the verge of ruin, he had written tohis brother the compradore for assistance. Hi An, a born gambler, likeevery Chinaman, had himself been speculating disastrously, and wasunable to give any help. But he had appealed to Mr. Brown, who had atonce advanced the sum required and set the grain merchant on his feetagain. The loan had long since been repaid: in business transactionsthe Chinaman is the soul of honour: but he had never lost his feeling ofgratitude; and his recollection of Mr. Brown's kindness, together withhis brother's request, made him willing to run some risk on behalf ofhis benefactor's son.

Jack talked long over the situation with his host. His object was toget to Vladivostok as soon as possible. Having no pass he could nottravel openly, and when breakfast-time came next morning his absencefrom the Moscow train would be discovered, even if it were not found outbefore; the news would be telegraphed to Harbin, and there wouldinstantly be a hue and cry. The Chinaman doubted whether this would bethe case; the train officials would be too anxious to screen their ownnegligence. Still, it would be unsafe for Jack to remain in Harbin; asfor himself, he saw no way of helping him.

"I must go by train," said Jack, "and secretly. Could I go hidden in agoods wagon?"

"That might be possible," said the Chinaman; "but goods trains are notfast; they are often delayed for hours and even days. The journey wouldtake a week, and though you might carry food with you, you would have toleave your hiding-place for water, and you could not escape discovery."

"Still, it may be that or nothing. Have you yourself any goods going inthat direction?"

"No. My business is chiefly to supply fodder to the Russians, moreespecially for horses that are being sent south. I completed a largecontract yesterday. One thing I can do. I can go to the station in themorning and learn what trains are expected to leave for Vladivostok.That is the first step. You will remain concealed in my house. Youwere not seen as you entered?"

"No. The street was clear."

"Then nobody but my wife and myself need know that you are here. I willdo what I can for you."

"Thank you! And if it is a question of bribery, you need not beniggardly."

The Chinaman smiled. He had not had dealings with Russian officials fornothing.

Jack was provided with a couch for the night, and, being very tiredafter his long journey and the excitement of his escape, he soon fellasleep. About five o'clock he was awakened by the Chinaman's hurriedentrance.

"It is all arranged, sir," he said, "but at a terrible price. A trainconveying horses is to leave for Vladivostok at seven. The sergeant incharge is well known to me: I have had dealings with him. All Russianscan be bribed; but this man--sir, he is an extortioner. Still, afterwhat you said, I made the bargain with him. You give him at once twentyroubles; you arrive safely at Vladivostok and give him thirty roublesmore. I tried to make him accept twenty-five for the second sum, but herefused."

Jack could not help smiling at this naive evidence of the oriental habitof bargaining. He felt that if he reached Vladivostok for fifty roubleshe would have got off remarkably well.

"But how is it to be managed?" he asked.

"I gave him to understand, sir, that you are a foreign correspondentwishing to see Vladivostok, and that there is a delay in the forwardingof the necessary authorization. It was because you are a foreigner thatthe sergeant was so firm about the five roubles. He talked about therisk he ran, and said that you must leave the train some time before itarrives at Vladivostok and walk the rest of the way. He said, too, thatif you should be discovered you were not to admit that he had anyknowledge of your presence. I promised that you would do all this."

"Very well. I am exceedingly obliged to you. But how am I to go? Whatwill the sergeant do for twenty roubles?"

"He will give you a corner in a horse-box."

"Does the train consist of nothing but horse-boxes?"

"Horse-boxes and the sergeant's van. You cannot go in that."

"No. And how am I to get into the horse-box without being seen? Thereare sure to be soldiers and officials about."

The Chinaman rubbed his hands slowly and pondered.

"If it had been yesterday," he said, "you might then have gone hidden ina hay-cart. But my last loads were delivered yesterday."

"Who knows that?"

"The inspector of forage; perhaps others."

"And is the inspector likely to be at the station this morning?"

"Not so early as seven; he is too fond of his bed for that."

"Where is the train standing?"

"On a siding at some little distance from the station. You can drivestraight up to it from the road through the goods entrance. But thereis a sentry at the gate."

"Well, Mr. Hi, I think I see a way to dodge the sentry, with your kindassistance. I suppose you have some hay or straw in your store?"

"Certainly."

"Then if you will load up a wagon with several large bundles, and leavea hole for me in the middle, I think I can get to my place in thehorse-box."

"But you might be seen as you slip out."

"We can lessen the risk of that. You can drive the wagon up to thehorse-box as though bringing a final load that had been overlooked. Iam covered by the bundles. You move them in such a way that the sides ofthe cart are well screened, at the same time leaving a passage for me.I ought to be able to slip into the box without being observed. And ifyou are willing I will chance it."

The Chinaman agreed, and as the time was drawing near, and the earlierthe plan was carried out the better, he went off to get his wagonloaded. Shortly after six the cumbrous vehicle was brought up as closeas possible to a door giving into the yard of the store. Jack thankedMr. Hi very warmly for his services, and begged him, if he should by anychance learn of Mr. Brown's whereabouts, to communicate with his brotherin Moukden. Choosing a moment when nobody but the Chi

naman and his wifewas near, Jack slipped into the wagon, and was in a few momentseffectually concealed by the bundles of hay. He found in the bottom ofthe cart a supply of food and a large water-bottle thoughtfully providedby his obliging host.

Mr. Hi himself mounted to the bare board behind his oxen, grasped therope reins in one hand and the long-thonged whip in the other, and droveoff. Jack did not enjoy the drive, jolted over the vile roads, andhalf-choked by the full-scented hay. The wagon came to the gate of thegoods entrance, and the Chinaman was challenged by the sentry. Hepulled up, and with much deference explained that he had brought a lastload of hay for the horses about to leave for Vladivostok, pointing atthe same time to the long line of horse-boxes standing on the siding,about three hundred yards away. The sentry jerked his rifle over hisshoulder and said nothing. Taking his silence for consent, the Chinamanlashed his oxen, and the wagon rumbled over the bumpy ground and two orthree lines of metals until it reached the last carriage but one, nextto the brake-van. The Chinaman jumped to the ground, backed the wagonagainst the door, and began to arrange his bundles as Jack hadsuggested. He whispered to Jack that nobody was near; and next moment aform much the colour of hay crept on all-fours out of the wagon into thevan. Then Mr. Hi built up the hay with what was already in the vehicle,so as to conceal him and yet allow a little air-space near one of thesmall windows. There were three horses in the van. Though earlymorning, it was already close and stuffy, and Jack looked forward withanything but pleasure to the heat of mid-day and the prospect of manyhours in this equine society.

Kobo: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War

Kobo: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War Frank Forester: A Story of the Dardanelles

Frank Forester: A Story of the Dardanelles Wizard Will, the Wonder Worker

Wizard Will, the Wonder Worker With Marlborough to Malplaquet: A Story of the Reign of Queen Anne

With Marlborough to Malplaquet: A Story of the Reign of Queen Anne The Dogs of Boytown

The Dogs of Boytown Brown of Moukden: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War

Brown of Moukden: A Story of the Russo-Japanese War Detectives, Inc.: A Mystery Story for Boys

Detectives, Inc.: A Mystery Story for Boys Bright Ideas: A Record of Invention and Misinvention

Bright Ideas: A Record of Invention and Misinvention Lost in the Cañon

Lost in the Cañon The Rival Campers Afloat; or, The Prize Yacht Viking

The Rival Campers Afloat; or, The Prize Yacht Viking The Flying Boat: A Story of Adventure and Misadventure

The Flying Boat: A Story of Adventure and Misadventure The Flying Reporter

The Flying Reporter Jack Hardy: A Story of English Smugglers in the Days of Napoleon

Jack Hardy: A Story of English Smugglers in the Days of Napoleon No Man's Island

No Man's Island The Motor Scout: A Story of Adventure in South America

The Motor Scout: A Story of Adventure in South America A Hero of Liége: A Story of the Great War

A Hero of Liége: A Story of the Great War Barclay of the Guides

Barclay of the Guides Carry On! A Story of the Fight for Bagdad

Carry On! A Story of the Fight for Bagdad Swift and Sure: The Story of a Hydroplane

Swift and Sure: The Story of a Hydroplane The Air Patrol: A Story of the North-west Frontier

The Air Patrol: A Story of the North-west Frontier Boys of the Light Brigade: A Story of Spain and the Peninsular War

Boys of the Light Brigade: A Story of Spain and the Peninsular War The Rival Campers; Or, The Adventures of Henry Burns

The Rival Campers; Or, The Adventures of Henry Burns Palm Tree Island

Palm Tree Island The Friends; or, The Triumph of Innocence over False Charges

The Friends; or, The Triumph of Innocence over False Charges Maggie's Wish

Maggie's Wish Tom Burnaby: A Story of Uganda and the Great Congo Forest

Tom Burnaby: A Story of Uganda and the Great Congo Forest Settlers and Scouts: A Tale of the African Highlands

Settlers and Scouts: A Tale of the African Highlands In Clive's Command: A Story of the Fight for India

In Clive's Command: A Story of the Fight for India Samba: A Story of the Rubber Slaves of the Congo

Samba: A Story of the Rubber Slaves of the Congo The Auto Boys' Quest

The Auto Boys' Quest Tom Willoughby's Scouts: A Story of the War in German East Africa

Tom Willoughby's Scouts: A Story of the War in German East Africa The Adventures of Harry Rochester: A Tale of the Days of Marlborough and Eugene

The Adventures of Harry Rochester: A Tale of the Days of Marlborough and Eugene Fighting with French: A Tale of the New Army

Fighting with French: A Tale of the New Army Round the World in Seven Days

Round the World in Seven Days The Adventures of Dick Trevanion: A Story of Eighteen Hundred and Four

The Adventures of Dick Trevanion: A Story of Eighteen Hundred and Four